Domain Boundary Conditions¶

Ideal Domain BCs¶

There are two primary types of physical/domain boundary conditions: those which rely only on the data in the valid regions, and those which rely on externally specified values.

ERF allows users to specify types of boundary condition with keywords in the inputs file.

The information for each face is preceded by

xlo, xhi, ylo, yhi, zlo, or zhi.

Currently available type of boundary conditions are

inflow, outflow, slipwall, noslipwall, symmetry or MOST.

(Spelling of the type matters; capitalization does not.)

For example, setting

xlo.type = "Inflow"

xhi.type = "Outflow"

zlo.type = "SlipWall"

zhi.type = "SlipWall"

geometry.is_periodic = 0 1 0

would define a problem with inflow in the low-\(x\) direction,

outflow in the high-\(x\) direction, periodic in the \(y\)-direction,

and slip wall on the low and high \(y\)-faces, and

Note that no keyword is needed for a periodic boundary, here only the

specification in geometry.is_periodic is needed.

Each of these types of physical boundary condition has a mapping to a mathematical boundary condition for each type; this is summarized in the table below.

ERF provides the ability to specify a variety of boundary conditions (BCs) in the inputs file.

We use the following options preceded by xlo, xhi, ylo, yhi, zlo, and zhi:

Type |

Normal vel |

Tangential vel |

Density |

Theta |

Scalar |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

inflow |

ext_dir |

ext_dir |

ext_dir |

ext_dir |

ext_dir |

outflow |

foextrap |

foextrap |

foextrap |

foextrap |

foextrap |

slipwall |

ext_dir |

foextrap |

foextrap |

ext_dir/foextrap/neumann |

foextrap |

noslipwall |

ext_dir |

ext_dir |

foextrap |

ext_dir/foextrap/neumann |

foextrap |

symmetry |

reflect_odd |

reflect_even |

reflect_even |

reflect_even |

reflect_even |

MOST |

Here ext_dir, foextrap, and reflect_even refer to AMReX keywords. The ext_dir type

refers to an “external Dirichlet” boundary, which means the values must be specified by the user.

The foextrap type refers to “first order extrapolation” which sets all the ghost values to the

same value in the last valid cell/face (AMReX also has a hoextrap, or “higher order extrapolation”

option, which does a linear extrapolation from the two nearest valid values). By contrast, neumann

is an ERF-specific boundary type that allows a user to specify a variable gradient. Currently, the

neumann BC is only supported for theta to allow for weak capping inversion

(\(\partial \theta / \partial z\)) at the top domain.

As an example,

xlo.type = "Inflow"

xlo.velocity = 1. 0.9 0.

xlo.density = 1.

xlo.theta = 300.

xlo.scalar = 2.

sets the boundary condtion type at the low x face to be an inflow with xlo.type = “Inflow”.

xlo.velocity = 1. 0. 0. sets all three componentns the inflow velocity, xlo.density = 1. sets the inflow density, xlo.theta = 300. sets the inflow potential temperature, xlo.scalar = 2. sets the inflow value of the advected scalar

The “slipwall” and “noslipwall” types have options for adiabatic vs Dirichlet boundary conditions. If a value for theta is given for a face with type “slipwall” or “noslipwall” then the boundary condition for theta is assumed to be “ext_dir”, i.e. theta is specified on the boundary. If no value is specified then the wall is assumed to be adiabiatc, i.e. there is no temperature flux at the boundary. This is enforced with the “foextrap” designation.

For example

zlo.type = "NoSlipWall"

zhi.type = "NoSlipWall"

zlo.theta = 301.0

would designate theta = 301 at the bottom (zlo) boundary, while

the top boundary condition would default to a zero gradient (adiabatic)

since no value is specified for zhi.theta or zhi.theta_grad.

By contrast, thermal inversion may be imposed at the top boundary

by providing a specified gradient for theta

zlo.type = "NoSlipWall"

zhi.type = "NoSlipWall"

zlo.theta = 301.0

zhi.theta_grad = 1.0

We note that “noslipwall” allows for non-zero tangential velocities to be specified, as in the Couette regression test example, in which we specify

geometry.is_periodic = 1 1 0

zlo.type = "NoSlipWall"

zhi.type = "NoSlipWall"

zlo.velocity = 0.0 0.0 0.0

zhi.velocity = 2.0 0.0 0.0

We also note that in the case of a “slipwall” boundary condition in a simulation with non-zero viscosity specified, the “foextrap” boundary condition enforces zero strain at the wall.

The keywork “MOST” is an ERF-specific boundary type; see MOST Boundaries for more information.

It is important to note that external Dirichlet boundary data should be specified as the value on the face of the cell bounding the domain, even for cell-centered state data.

Real Domain BCs¶

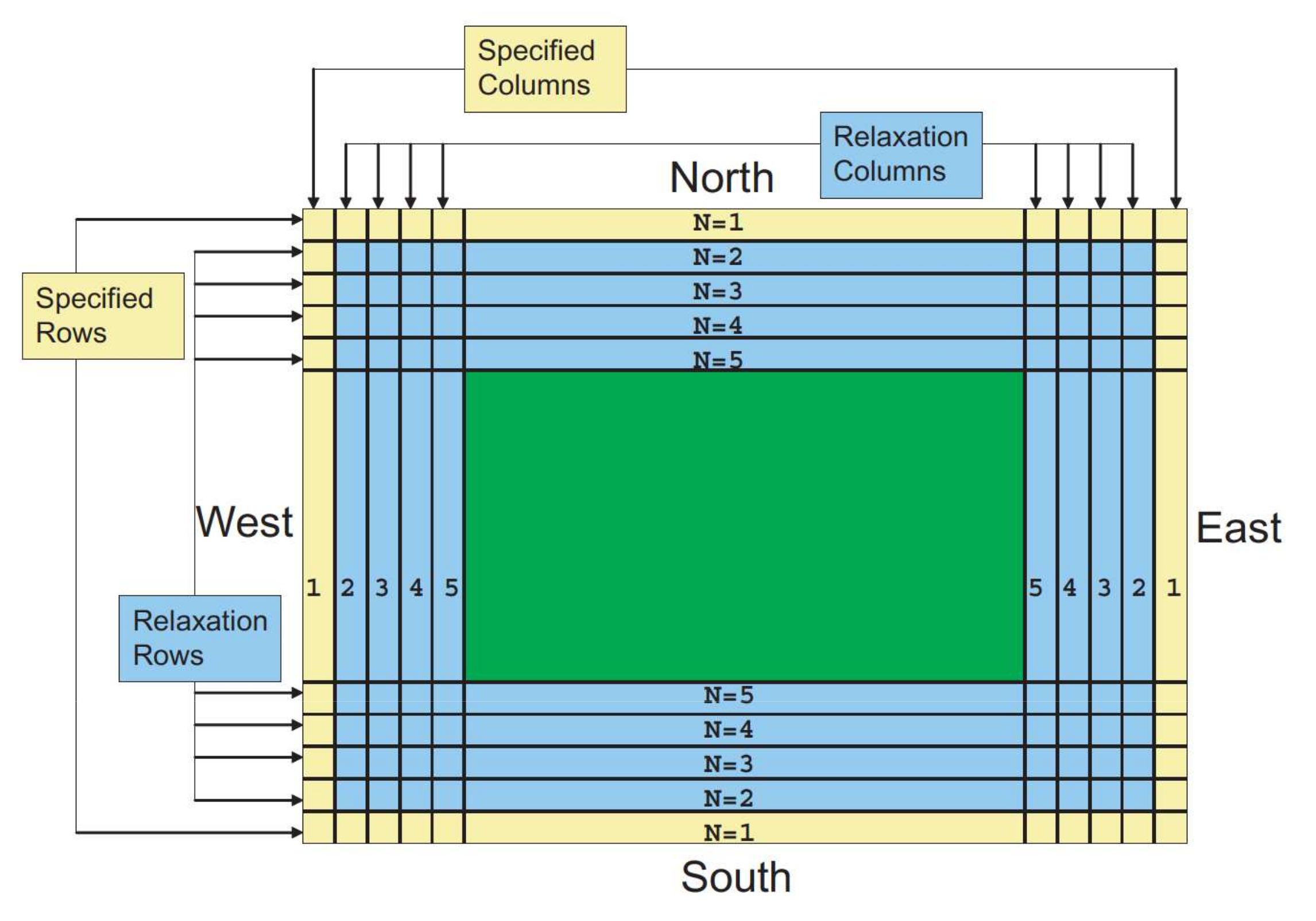

When using real lateral boundary conditions, time-dependent observation data is read

from a file. The observation data is utilized to directly set Dirichlet values on the

lateral domain BCs as well as nudge the solution state towards the observation data.

The user may specify (in the inputs file)

the total width of the interior Dirichlet and relaxation region with

erf.real_width = <Int> (yellow + blue)

and analogously the width of the interior Dirichlet region may be specified with

erf.real_set_width = <Int> (yellow).

The real BCs are only imposed for \(\psi = \left\{ \rho; \; \rho \theta; \; \rho q_v; \; u; \; v \right\}\).

Due to the staggering of scalars (cell center) and velocities (face center) with an Arakawa C grid,

we reduce the relaxation width of the scalars \(\left\{ \rho; \; \rho \theta; \; \rho q_v \right\}\) by 1

to ensure the momentum updates at the last relaxation cell involve a pressure gradient that is computed with

relaxed and non-relaxed data.

Image taken from Skamarock et al. (2021) |

Within the interior Dirichlet cells, the RHS is exactly \(\psi^{n} - \ps^{BDY} / \Delta t\) and, as such, we directly impose this value in the yellow region. Within the relaxation region (blue), the RHS (\(F\)) is given by the following:

where \(G\) is the RHS of the Navier-Stokes equations, \(\psi^{*}\) is the state variable at the current RK stage, \(\psi^{BDY}\) is temporal interpolation of the observational data, \(C_{01} = -\ln(0.01) / ({\rm RealWidth - SpecWidth})\) is a constant that ensure the exponential blending function obtains a value of 0.01 at the last relaxation cell, and \(n\) is the minimum number of grid points from a lateral boundary.

Sponge zone domain BCs¶

ERF provides the capability to apply sponge zones at the boundaries to prevent spurious reflections that otherwise occur at the domain boundaries if standard extrapolation boundary condition is used. The sponge zone is implemented as a source term in the governing equations, which are active in a volumteric region at the boundaries that is specified by the user in the inputs file. Currently the target condition to which the sponge zones should be forced towards is to be specifed by the user in the inputs file.

where RHS are the other right-hand side terms. The parameters to be set by the user are – A is the sponge amplitude, n is the sponge strength and the \(Q_\mathrm{target}\) – the target solution in the sponge. \(\xi\) is a linear coordinate that is 0 at the beginning of the sponge and 1 at the end. An example of the sponge inputs can be found in Exec/RegTests/Terrain2d_Cylinder and is given below. This list of inputs specifies sponge zones in the inlet and outlet of the domain in the x-direction and the outlet of the domain in the z-direction. The start and end parameters specify the starting and ending of the sponge zones. At the inlet, the sponge starts at \(x=0\) and at the outlet the sponge ends at \(x=L\) – the end of the domain. The sponge amplitude A has to be adjust

ed in a problem-specific manner. The density and the \(x, y, z\) velocities to be used in the sponge zones have to be specified in the inputs list.

erf.sponge_strength = 10000.0

erf.use_xlo_sponge_damping = true

erf.xlo_sponge_end = 4.0

erf.use_xhi_sponge_damping = true

erf.xhi_sponge_start = 26.0

erf.use_zhi_sponge_damping = true

erf.zhi_sponge_start = 8.0

erf.sponge_density = 1.2

erf.sponge_x_velocity = 10.0

erf.sponge_y_velocity = 0.0

erf.sponge_z_velocity = 0.0

Another way of specifying sponge zones is by providing the sponge zone data as a text file input. This is currently implemented only for forcing \(x\) and \(y\) velocities in the sponge zones.

The sponge data is input as a text file with 3 columns containing \(z, u, v\) values. An example can be found in Exec/SpongeTest and a sample inputs list for using this feature is given below. This list specifies a sponge zone in the inlet in the x-direction. The \(u\) and \(v\) velocity forcing in the sponge zones will be read in from the text file – input_sponge_file.txt.

erf.sponge_type = "input_sponge"

erf.input_sponge_file = "input_sponge_file.txt"

erf.sponge_strength = 1000.0

erf.use_xlo_sponge_damping = true

erf.xlo_sponge_end = 4.0